caring and nonchalance

the parts of ourselves we hide from others

I’m someone who respects authority. It’s not a trait that I’m particularly proud of. It’s closely linked to conscientiousness, which I don’t like to admit to either, even though every success I’ve achieved is owing to it. Getting a good job out of college was the result of working my butt off as an intern and knowing my place in the corporate hierarchy. Completing three novels would not have been possible without waking up early every morning to write before work.

Conscientiousness has taken me far. Yet, I’m embarrassed by it. I think this has to do with the fact that diligent effort is so undervalued in our culture, sometimes even scorned. We prefer to make things look effortless. We adore rebels and mavericks. Kids who put in a lot of effort without payoff are “losers.” It’s cool to be cool, to act like you don’t really care about the result. This air of nonchalance is driven by a deep fear of rejection. We’re afraid to look like we’re taking ourselves too seriously because what if we fail? Somehow, it’s less shameful to fail without having put in much effort.

We hide our ambition, too. There’s a Freddie Mercury quote I really like: “My songs are like Bic razors. For fun, for modern consumption. You listen to it, like it, discard it, then on to the next. Disposable pop.” I love the idea that you shouldn’t be too precious about your art. It can get in the way of creating art. But the sentiment is misleading. Freddie may have said it in an attempt to ward off expectations or deter reporters and fans from overanalyzing the lyrics. I don’t think he actually thought his songs are disposable. No one with that kind of success truly feels that way about their art.

It’s interesting to look at performative nonchalance through the lens of status games. We naturally play high or low status depending on whether we want to appear more or less of a threat to the people around us.

From Keith Johnstone’s Impro:

A person who plays high status is saying “Don’t come near me, I bite.” Someone who plays low status is saying, “Don’t bite me, I’m not worth the trouble.” In either case the status played is a defence, and it’ll usually work. It’s very likely that you will increasingly be conditioned into playing the status that you’ve found an effective defence.

I prefer to play low status at work, to obey authority, because it has generally gotten me what I’ve wanted (praise, more interesting work) and helped me avoid what I don’t want (rebuke, getting fired). But constantly playing low status is limiting. Maybe the promotion I’m hoping for is out of reach because people perceive me as someone who’s not particularly ambitious, who lacks “executive presence” (a term I find very problematic, but that’s another topic). Once I’m aware that I can play high status—that I can alternate between the two depending on the situation—a whole new set of actions and language is available to me, along with new results.

Coolness, nonchalance, indifference are all postures of high status. There’s the classic trope of the boy feigning indifference toward the girl he likes in front of his guy friends (e.g. Danny in Grease). We obsess over the person we like when they’re not there, and in their presence, we dial it all the way down until it looks almost like indifference because we’re afraid of romantic (and social) rejection.

There was a time I waffled about texting a guy because I didn’t want to come across as needy. I didn’t want him to think I cared too much. It seemed safer to feign indifference, to not text him, to wait and see if he would text me first. But as you can imagine, my attempt to suppress my needs only made me more anxious. I was working with an ontological coach at the time, and he introduced me to the OAR model.

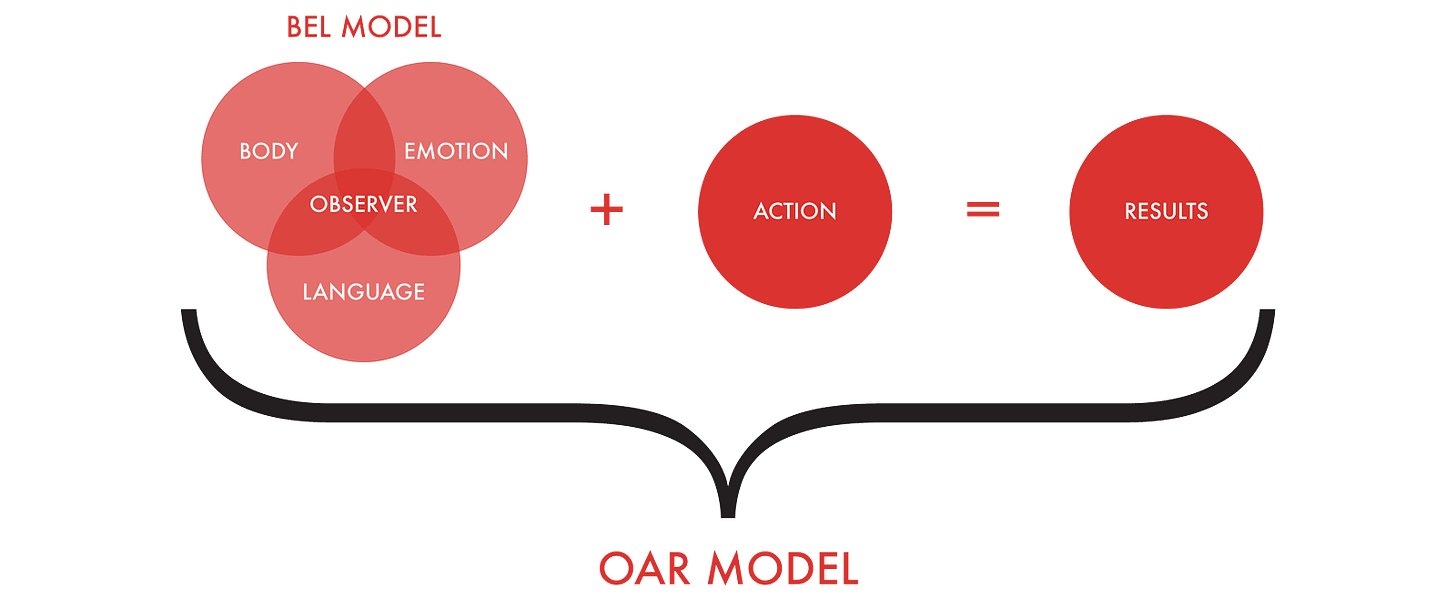

Often, when we try something, and it doesn’t produce the desired result, we try a different action. This is first order learning. We don’t realize that the set of actions available to us is limited by our observer (how we see ourselves and the world around us). If we’re able to change our observer, we can broaden the range of actions available to us.

So how do you change your observer? You experiment with your body, emotions, and language. One way to do this is to switch between playing high and low status. If you can identity the status you’re currently playing, you can switch to the other status, and you can do this through your words, emotions or how you carry yourself. Maybe you try using different words, but it doesn’t quite translate into a new state of being, so you try different body language or expressing a different emotion. The goal is to unlock a new coherence of body, emotions, and language (BEL).

A big aha for me was coming across the concept of vertical vs. horizontal relationships in Adlerian psychology via the book The Courage to be Disliked. Instead of treating relationships as vertical in which one person has the higher status due to characteristics like age, gender, experience, rank, etc., we treat all relationships as essentially equal.

As someone who has a tendency to seek praise from teachers, bosses, parents and avoid criticism and rejection, I find this idea powerfully transformative. Treating these people as my equals would change how I engage with them (my body, emotions, language) and consequently how I perceive myself and the world around me (my observer).

In the case of the person I was afraid to text, underlying this fear is the belief that he holds more power because he has the ability to judge me. But the ability to judge goes both ways, so I should just conduct myself in the way that feels most natural instead of worrying about how he’ll perceive me.

Treating relationships as horizontal allows for fluidity: one person plays high status, the other plays low, and you can switch. There’s a constant back and forth, a conversation. Vertical relationships assume a static role for each person, which limits how far the interactions can go.