luck

the narratives we choose to believe

I was in London for work last week and went to Paris for the long weekend with the intention of being the most productive and taking a big swing at revising my novel. After all, I’ve done all the touristy things, so what else was there to do but sit in cafes and write?

Of course, I didn’t take into account that the last time I was in Paris was a full decade ago (!), and so, there was a lot for me to rediscover. On the first day, I had the romantic notion of parking myself in a cafe in Montmartre to do a couple of hours of work before lunch, but I got distracted by all the side streets and vintage shops and street performers and ended up browsing and walking around and being a total flâneur instead of sitting my butt down. The next day, abandoning any pretense of writing, I left my laptop at the hotel and revisited some of my favorite spots: a popular crêperie in the Marais (Breizh Café) where I enjoyed a galette washed down with cidre de Bretonne and Père LaChaise cemetery where I snacked on French strawberries while strolling amid the tombstones of Proust, Colette, and Balzac, thinking about how the passage of time makes it easy to romanticize people and places.

This was my fourth trip to Paris. There are so many places in the world I want to see. Why waste a train/plane ticket and precious vacation days on a city I’ve already visited three times? What I’ve come to understand, though, is that places are like people: once you fall in love with a city, you can never get sick of it because it’s always going to reveal something new to you. Even if the city itself hasn’t changed, you will find something new to appreciate because your perspective has shifted. You notice features that were previously invisible to you.

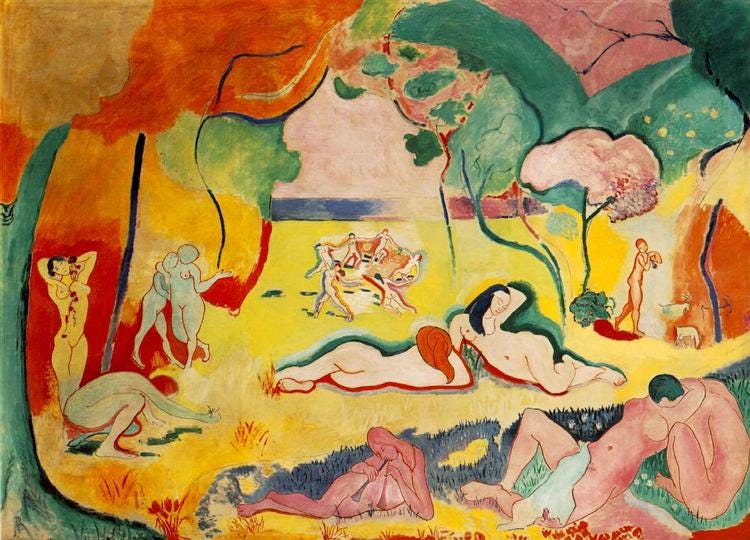

On this trip, I found myself gravitating toward modern art instead of Monet and Manet and seeking out quieter, residential neighborhoods. I wandered north from my hotel and stopped for pho at an unassuming Vietnamese restaurant, then read for a bit in Parc Monceau, now my favorite green space in Paris.

I was telling my friend Maia that I don’t see myself leaving New York despite the fact that it’s ridiculously expensive, and Europe is arguably a better place to spend your hard-earned money. Because I love New York, I can easily overlook its flaws. I think you have to be somewhat irrational in order to commit to a person or a place. I don’t fall in love easily, but when I do, I’m all in. And so, to me, New York is simply the best city in the world, no questions asked.

My feelings about Paris are somewhat more complicated. I took French from fifth grade through college and was just a few credits shy of graduating with a minor. The first time I visited was on an exchange program where I lived with a host family in the countryside, went to school with their daughter, and found myself the object of great curiosity among provincial French boys. On my second trip, a girl selling trinkets stopped me at a crosswalk in Champs-Elysées, and when I declined whatever she was offering, she yanked my arm angrily, and my friend yelled get away from her, and pulled me in the other direction (I experienced the incident as a bewildering tug-of-war). Within the next hour, I had my iPhone pickpocketed. No matter how much French I’ve taken, how gently I roll my “r’s,” I will always be seen as an outsider in this city. Maybe it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: the less you feel like you belong, the more you look like a tourist.

On my first day back in Paris, a man wearing a leather satchel approached me and asked if I spoke English. He said he was from Milan and that he had been pickpocketed in the metro and lost his phone and wallet. Oh no, I’m so sorry, I said. I know exactly how that feels. He kept going on about his hardship, and when I asked how I could help, expecting him to ask for directions to the police station or the Italian embassy, he begged for 20 euros so that he could get a hotel room. Suddenly, I realized I’d heard this story before—as a cautionary tale. The shutters came down, and I walked away.

As we move through life, we choose which narratives we want to believe. We choose who to let in and how wide to open the door. And there is no right answer—or rather, the right answer cannot be known a priori. In Lisa Jewell’s thriller None of This is True, the main character, Alix, meets a woman named Josie who tries to inveigle her way into Alix’s life. Josie tells a disturbing and outlandish story about her family that would arouse mistrust in others, but inspires sympathy in Alix who goes out of her way to help her, even inviting her into her home.

Are you the type of person that trusts others by default or do people have to earn your trust? This is a common question on personality tests. You can never know with 100% certainty if someone can be trusted. And like love, trust is not something you can do halfheartedly. You either trust someone or you don’t, which is why you can never blame yourself for failing to see the warning signs before a relationship ends.

“Do you think you’re lucky?” Maia asked as we sat and talked for six hours in a cafe in the 11th. Because people who think they are lucky tend to invite luck, and people who don’t, don’t. Our beliefs about ourselves shape our reality. When you’re in a new country, you can have your guard up all the time, expecting to be taken advantage of, or you can be extremely optimistic to the point of self-delusion (both, by the way, are common survival strategies among immigrants). I think a fundamentally positive outlook is much healthier than a misanthropic one, as long as it’s balanced out by equal parts common sense and intuition, which can only be honed through experience. And not just firsthand experience, but the experience we gain from hearing other people’s stories. The narratives we choose to believe get stored as knowledge.

I love your writing style. How beautifully you invite me to your life stories and share some learnings in between so subtly