materialists

love in the time of capitalism

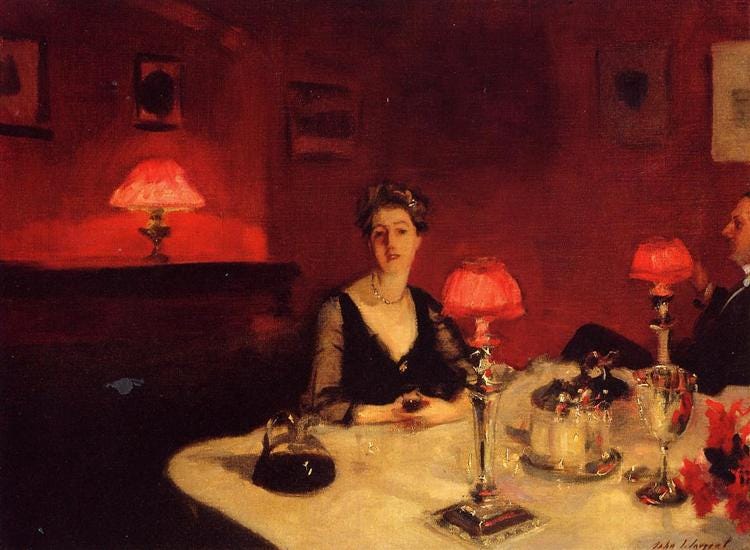

A girl I went to college with would exclusively date men who took her to Michelin-starred restaurants. She would otherwise complain if it was just a really nice fine-dining place. I found this utterly ridiculous. At 21, I couldn’t see what Per Se or Eleven Madison Park had anything to do with love. Turns out, there’s a whole world of people who put a lot of stock in economic status, and being wined and dined at a certain type of establishment signals economic and cultural capital. It’s their love language.

Celine Song’s Materialists opens with a silent scene in which a caveman gives his sweetheart a ring fashioned from a daisy. He slips it onto her dirt-stained finger. They smile, and you can tell that they’re really happy together. In prehistoric times, the film shows us, love was simple.

Fast forward 300,000 years, and we’re swiping on apps, doing mental gymnastics to figure out what a one-word text means, calculating our relative value on the “dating market,” getting all kinds of bodily work done to increase our attractiveness—and still, with all that effort, love escapes us. As Pedro Pascal’s character bemoans, love is the hardest, most elusive thing in the world. (It’s truly become a first-world problem.)

Just like Song’s first film Past Lives, Materialists features a choice between two suitors who serve as archetypes, representing different value systems. Lucy must choose between the broke, struggling-actor ex-boyfriend living with two roommates and a private equity honcho who owns a $12 million Tribeca penthouse. Unlike Nora, Lucy chooses with her heart. She ditches the rich guy, turns down a promotion, and quits her matchmaking job. She breaks out of the system and makes the “correct” choice in the moral universe of the film.

I think it’s overly simplistic to conclude that capitalism is antithetical to finding love, or that love should be unaffected by materialistic concerns. Who’s to say that our Stone Age ancestors didn’t vie for the affection of the strongest, fastest, cleverest hunter who brought back the most game? Or that my friend from college didn’t find genuine happiness and love with a high earner and fine dining enthusiast?

There’s a scene in the movie where one of Lucy’s clients has a nervous breakdown right before her wedding. Lucy asks her what she likes about her tall, handsome, wealthy husband-to-be, and she very honestly says, “He makes my sister jealous.” Lucy concludes that he makes her “feel valuable,” which puts a smile back on her face and settles any doubts. For one person, feeling valuable can mean being treated to fancy meals and vacations. For another, it can mean receiving back massages and a sympathetic ear after a hard day. It can also mean both.

Who we fall in love with is ultimately a reflection of what we value individually and how we view ourselves. There’s no escaping yourself in dating. No matter who you’re sitting across from, the one constant you come up against is your own insecurities, your own unresolved issues, your own doubts and fears.

A prospective suitor finding Sophie unattractive (“she’s 40 and fat”) says more about him than it does about her intrinsic worth. But as the matchmaker, Lucy can’t help but view this as a sign that her client isn’t “competitive in the dating market,” just as an algorithm might ding her for getting passed on.

Algorithms can predict who will get the most dates based on a few salient facts (height, fitness, age, hairline, income, etc.), but they can’t predict who we’ll fall in love with. Dating is the imprecise, unscientific mechanism through which we try to find love. As Celine Song says on The Modern Love podcast, what makes love hard is that you have no control over it, and in the modern world, all we want to do is exert control:

Go to the gym, botox, right? Everything is there so that it can increase your value in the stock market of dating. I wish that all of those efforts actually resulted in love. But I think we all ultimately know the truth, which is that none of them has anything to do with whether you’re going to fall in love. You might be in front of somebody who is perfect for you in every way and feel nothing. And you might be in front of someone who is imperfect in every way, and you just feel everything.

I wish the movie explored more fully what Lucy loves about John and vice versa. Instead, we’re expected to take their attraction as a given. We can imagine that John’s dogged pursuit of his acting career is something Lucy admires about him, a contrast to her practical, self-described “cold” and “materialistic” nature. On his part, he tells her that she inspires him to work harder and earn more, take on more catering jobs and even do dreaded commercials. (Very cute.)

If there’s any truth about love that the movie reveals, it’s this: the people we fall in love with often reveal to us untapped possibilities in ourselves, along with all of our good, bad, and ugly. The love we find, the love we accept, is the truest mirror onto our own hearts. Sometimes, we run away from what we see (like Lucy did with John the first time they broke up).

Sometimes, we stay.

"the people we fall in love with often reveal to us untapped possibilities in ourselves" - Yes, I've found this to lead to unexpressed desires/dreams that were difficult to admit, and areas of my life that were not getting enough attention. In the IFS framework, this led to parts that were not being heard.

Such a simple question: "what *about* her makes me feel so alive?" -> art, adventure etc. when those things were missing in my life

Thanks for this piece!

What ended up happening to the woman who only went to Michelin starred restaurants? Did she have a turn like in the movie and marry a middle class (or lower) guy or did she stay in rich world forever?