My shadow is causing problems for my book.

At first, I thought it was a plot problem. After spending nine months revising my manuscript, I sent it back to my agent, happily closed all my tabs, and turned my sights to new projects, only to hear back, a couple of weeks later, that the execution is still not landing. It doesn’t read like a thriller. The tension is still not escalating.

In a panic, I started overhauling the plot, on a tear to escalate the shit out of tension. I studied some of my favorite books and movies in the genre (Sea of Love is a gem) and mapped out every scene: what we learn, what we think is happening, what the MC (main character) thinks is happening, what is really happening. I stared at my scene spreadsheet for many dizzying hours, then whacked and hacked at my plot.

It wasn’t until this past weekend, over book therapy lunch with my friend Crystal, that I had a breakthrough. The problem isn’t plot—rather, plot isn’t the root of the problem.

I told C I had a hard time writing my main character because I didn’t really like her. “Why is that?” she asked. I couldn’t give a straight answer. The thing I dislike about her is hard to pinpoint. In earlier drafts, her vulnerability made her kind of depressing for me to write. I wanted to respect her, to admire her, but I couldn’t. I had this urge to make her more savvy, more street smart, more cunning. Better to be shrewd and guarded in this cruel world than naive and yearning.

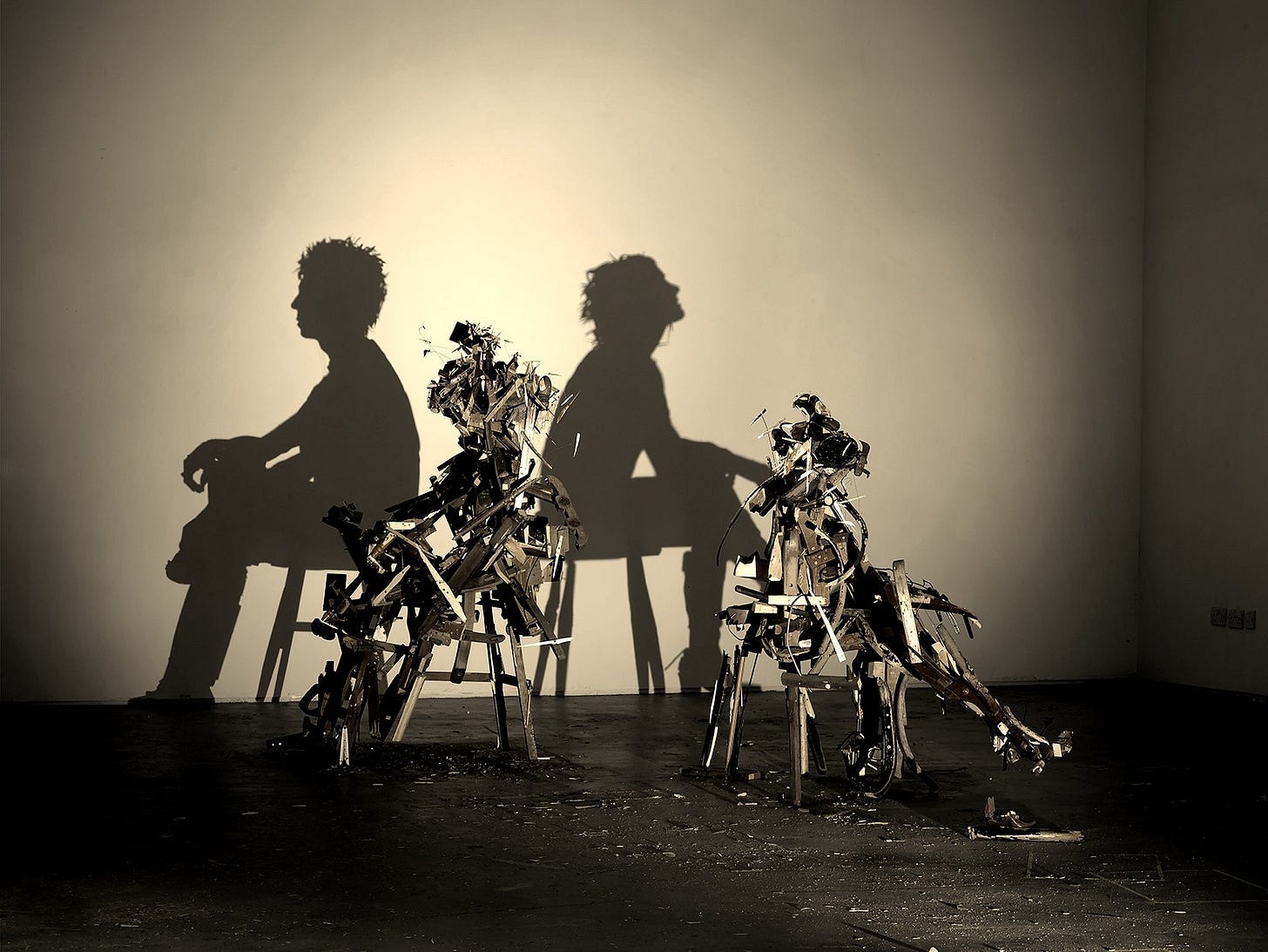

C asked if I would consider writing my book in first person POV rather than close third. I balked. First person, in my opinion, is overused and runs the risk of self-indulgence. But C pointed out that this is probably what my book needs: more character depth. The plot feels forced because the character isn’t fully there. She’s a “silhouette.” We get biographical information about her (family dynamics, socio-economic class)—and she carries a boatload of trauma—but we don’t really know her. I write about how she thinks and feels, of course. But upon re-reading my pages, I noticed that there’s something detached and standoffish about her interiority. My agent said she wouldn’t be able to say how my MC would react in a given situation. But if you take any memorable TV character, say George from Seinfeld, you would know immediately how he’d respond in any scenario. You would hear his voice in your head.

My character’s voice lacks body. Her observations aren’t unique to who she is. That’s because I’m resisting getting close to her. My “protectors” (in IFS terms) are reacting to her youth. My manager parts don’t want to expose her exiles on the page, which, not incidentally, are my exiles, my shadow. Every time I dip into her psyche, I stay there for a hot second, then jump back out and return to my authorial voice of moving the plot along. She has become a vehicle for the story rather than the source of the story. My judgment is making me unable to see her complexities.

My character is twenty-two. When I was that age, I partied like it was no one’s business. I was reckless. I made dumb decisions. I craved acceptance. I wanted to look and feel a certain way. I wanted to be seen and desired by men, but God forbid I came across as attention-seeking. I was, like many young people out of college, extremely impressionable and vulnerable. Where I sought external validation in my twenties, I now value individuality and self-assurance. It’s almost a complete reversal. But instead of integrating who I was, I’m running away from her, and by extension, my character. I’m holding her at arm’s length.

That’s why it feels depressing to step into her shoes. It’s like being twenty-two again and saying, I want you to see me just as I am. Words I absolutely could not say back then without embarrassment and shame. Words I still can’t say today.

Amidst these creative challenges, there has been no better time in my life to read Tiny Experiments by neuroscientist and entrepreneur Anne-Laure Le Cunff. I am a perpetual work in progress, as is my book, and I love that Tiny Experiments brings a mindset of curiosity and experimentation to life and work. In the spirit of experimenting, I commit to spending one hour each day for a week writing from my character’s first person point-of-view. It’s going to feel uncomfortable, but it might unlock something about her. That doesn’t mean I’m going to switch to first person entirely. The beauty of experimenting is that I can try it, assess what’s working and what’s not, then decide on the next step.

I’d love to hear from you in the comments: Have you integrated your shadow? Does it show up in your creative work?

That first sentence hooked me, also never thought about shadow work in this application before. It's very cool, although... why not make the main character cunning? Love an anti-heroine that makes smart decisions, even if the decisions end up being naive because they're made without complete information.