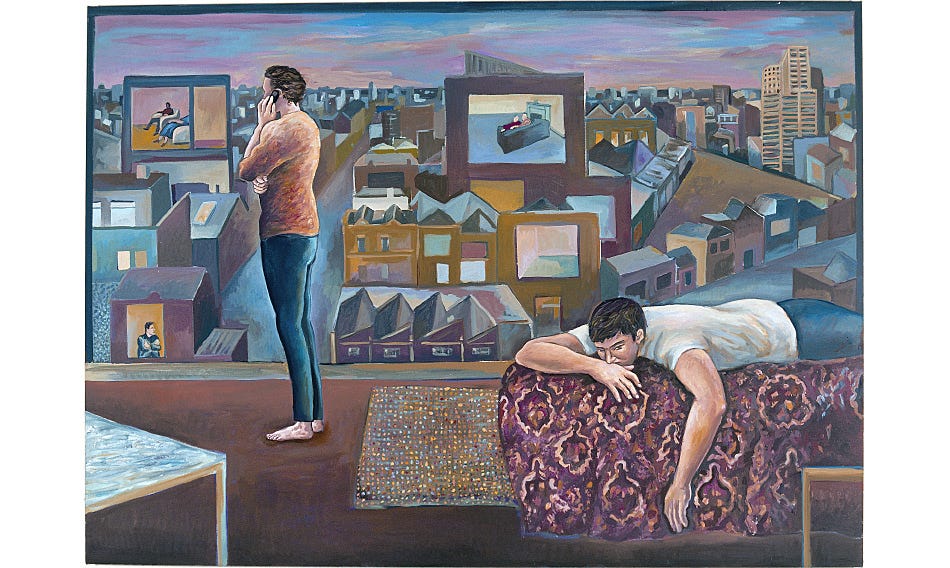

Why do people stay attached to conventional good-life fantasies—say, of enduring reciprocity in couples, families, political systems, institutions, markets, and at work—when the evidence of their instability, fragility, and dear costs abound?

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism

I’ve been thinking a lot about reciprocity. Is it fair to expect the important people in my life—friends, people I’m dating, family—to invest equally in our relationship? I want them to text me as often as I text them. But isn't it more secure to just text someone whenever I feel like it (don't overthink it, don't keep score)? When someone I like doesn’t initiate, does it mean they are ambivalent about me, and therefore, I should take a step back or completely remove them from my life?

The older I get, the more my friends have dispersed across the country or moved abroad. It takes a lot of effort to maintain a friendship when you don’t see each other regularly. People get married, settle down, have children. We’re living busier lives. It’s so easy to grow apart. In fact, it’s the default state. When we were younger, we expected friendships to be effortless. We made friends and stayed friends because we were in the same class. It was so simple, so uncomplicated. But as we get older, more effort is required to keep a friendship going. So, when I reach out to someone to hang out, I’m hoping that next time, they’ll be the one reaching out to me.

Maintaining a long-distance friendship is just as hard as maintaining a long-distance relationship. It’s a skill, and some people are not great at it. They might be less proactive by nature, they might have a tendency to only see what’s in front of them (out of sight, out of mind) or they might be so accustomed to other people taking the lead that they don’t think to initiate.

But sometimes, they don’t initiate because they’ve found a new circle of friends, and if you’re not part of that circle, you’re no longer a necessary part of their life. This doesn’t mean they don’t like you or care about you. It just means they’re driving a car with new people in it, and you’re driving your own car, and although you can cross paths, you don’t need to because you’ve got your own cars and your own passengers and your own adventures. And that’s O.K. But what’s hard is distinguishing between the two situations: how do I know if this friend has moved on or if they’re just not good at the whole reaching out thing?

In dating, it’s a different calculus. When someone doesn’t put in the effort to see you, it’s bad. There are no ifs, ands or buts. I can’t count the number of times I’ve analyzed a boy’s sparse texts to death as if they were verses of great Modernist poetry. No, there is not some deeper meaning in the words, and yet I can’t help but search for it. In college, my friends and I used to gather around in our common room and pore over texts from the guys we liked. It was fun but also highly pointless. If you find yourself having to speculate about someone’s intentions, chances are they’re not as interested as you’d hope.

But in dating, some people play “hard to get,” which makes communication, a thing that should be easy to understand, incredibly difficult and opaque. The thing to understand is that you don’t need to allow these people to complicate your life. You can choose complexity or you can choose to cut that shit out. That’s something I learned the hard way because, as a writer, I’m drawn to complexity. It’s catnip for my imagination.

My experience dating has been that you can’t feign enthusiasm, but some people have a way of presenting themselves that can be mistaken for interest when what it really is is good manners. I once dated a guy who gave me the impression that he was deeply interested in me. All the little things he did made me feel fantastic: the way he looked at me, asked thoughtful questions, showed sympathy, smiled, showed consideration, showed tenderness, etc. He was just being polite, and this was only made obvious in the span of time between dates when he rarely texted. Of course, being the anxious and hopeful person I was, I overanalyzed the rare texts he sent while ignoring the plain truth that he just wasn’t as invested as I was. Sure, there was mutual attraction and chemistry, but that doesn’t translate into effort and investment. Where I saw deeper interest was actually just impeccable manners, and manners can be very seductive.

It’s pretty easy to smile, ask good questions, and flirt when you’re on a date. It takes a lot more effort to keep a conversation going when you’re not face to face, when you get slammed at work, when life gets in the way. And in a city like New York where the choices are (seemingly) inexhaustible, it’s not enough to like someone, you have to think they are a rare bird and see future potential to put in the effort required to keep a new relationship going.

The stronger and longer the bond, the less reciprocity is needed to feel secure. With more recent relationships (e.g. someone you just started dating), it’s fair to expect more reciprocity because you don’t know the person well enough. You need them to demonstrate a certain amount of investment before you can get to the point where you think, alright, even though A is not initiating as much as I’d like, I know A cares about me, and we always have a good time when we’re together, so that’s O.K.

So far, I’ve been using “reciprocity” to mean mutual, demonstrable investment in a relationship. But that’s not the only way to define it. For Simone de Beauvoir, reciprocity is about recognizing each individual as both subject and object. There can be authentic asymmetrical relationships when we accept that we each have the freedom to choose how to live our lives. Beauvoir herself had an asymmetrical friendship with Zaza Lacoin, her best friend from childhood. The friendship meant so much more to Beauvoir than it did to Zaza, and Beauvoir was O.K. with this because she got so much meaning out of the relationship: Zaza helped her realize her full potential and see a new way of being in the world that was bountiful and exciting.

So, to return to my original question: is it fair to expect the important people in my life to invest equally in our relationship? Beauvoir would say that this expectation restricts other people’s freedom and fails to recognize their subjectivity. Instead, we should ask, why is this relationship so important to me and what am I getting from it? If it’s enriching my life, I can be fine with the asymmetry. I don’t need the other person to value the relationship equally. That need comes from a place of insecurity. Maybe what it really is is a need for validation. But it’s so hard: who doesn’t want a person they care deeply about to care as deeply about them in return?

The topic of reciprocity in relationships always brings to mind a certain stanza by W. H. Auden:

“How should we like it were stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.”

“Instead, we should ask, why is this relationship so important to me and what am I getting from it? If it’s enriching my life, I can be fine with the asymmetry.”

(Nothing below is meant to apply to you specifically, if I refer to “you” I just mean some third party. I’m just speaking generally on the topic of people/attachments)

This is setting off alarms for me. I would say that if you are asking yourself whether an asymmetric relationship is fulfilling/enriching then you are almost certainly not healthy/happy in it.

Behaviors are more important than thoughts, and sometimes the act of thinking is the behavior.

“Yeah he doesn’t seem interested in me, but he does have all these other traits I like, and I’m really interested in him. Am I really happy here?” If you even pose the question to yourself that’s a strong sign you might not be in a healthy relationship.

If you are more attached than they are, and you are okay with it, then you are letting someone have the power to disproportionately hurt you.

But why would you do that? Why would you give them that power? It makes for good literature but a bad life. The fact that you look to Beauvoir as an example supports that point.

We all want the more dramatic romance at a certain level. I believe one can want/crave/be drawn to an asymmetric enriching relationship but I think part of that enrichment is because of how it makes the subject feel being in such a relationship. Maybe being in a situation where one gets to stress/introspect on the relationship is the reward. Especially if it’s the default state for a person. But just because a person craves/is drawn to that state doesn’t make it healthy.